I'd like to wish all my readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! I'll be back in 2018 with more blog posts about social history.

If you pop over to my Jane Austen blog, you can read about the fun the Austen family had with their Christmas theatricals.

Illustration by Cecil Aldin, courtesy the Wellcome Library.

I'm an author specialising in family history, social history, industrial history and literary biography. Real stories; real people; real lives.

Search This Blog

Friday, 15 December 2017

Friday, 1 December 2017

A Georgian Heroine: Eleanor Coade

|

| Coade Stone Factory, Narrow Wall, Lambeth, anonymous, 1790s. |

Today I'd like to welcome back fellow Pen & Sword authors Joanne Major and Sarah Murden to my blog! They have a fascinating new book out, which you can order here!

Here's Sarah and Joanne's blog post:

Eleanor Coade (1733-1821)

Eleanor Coade was an

extremely successful businesswoman during the Georgian era, something which was

highly unusual. It seems likely that she inherited her business acumen from her

grandmother, Sarah Enchmarch, a formidable woman from Tiverton, Devon who took

over the running of the family textile business for some twenty-five years

following the death of her husband, Thomas in 1735.

|

| Coade Stone Factory yard on Narrow Wall Lambeth c.1800 by Shepherd. |

On reading Sarah

Enchmarch’s will (proved in 1760), it is clear that as well as providing for

her sons, she wanted to ensure that her six daughters were well provided for

and that the legacies they received were to be for their use, exclusive of

their husbands or future husbands. Sarah also left a legacy of five hundred

pounds for her two Coade granddaughters, money that would be invaluable to

Eleanor when she came to establishing her own business.

Eleanor is noted for

the invention of a product known as Coade Stone, also called Lithodipyra; the

secret of its manufacture endures to this day. She ran her very successful

manufacturing operation for over fifty years by the King’s Arms Stairs on

Narrow Wall in Lambeth, having taken over the ailing artificial stone business

of a Daniel Pincot in 1769.

You rather get the

impression that Eleanor was not a woman to be trifled with and she certainly

stood her ground, as shown in the Public Advertiser of September 1771, when she

wanted to make it very clear that Daniel Pincot was certainly not the owner of

the business, despite rumours to the contrary.

|

| Eleanor Coade trade card |

Whereas Mr Daniel

Pincot has represented himself as a partner in the Manufactory conducted by

him, ELEANOR COADE, the real proprietor, finds it needful to inform the public

that the said Mr Pincot is no other than a servant to her and that no

contracts, or agreements, discharges or receipts will be allowed by her, unless

signed by herself.

The product Eleanor

developed was described in a sales brochure for her showroom which opened in

1799, as giving ‘durability resembling Jasper and Porphyry. Frost and Damps

have no effect upon it, consequently it retains a sharpness not to be

diminished by the changes of climate’.

|

| View of Westminster Bridge, from Kings Arms Stairs, Narrow Wall, Lambeth - YBA |

Every piece of stone

sent out had the name COADE indented on it, effectively copyrighting Eleanor’s

work. She was certainly not backward in coming forward in promoting her product

and the brochure listed numerous places across Britain where you could see

examples of her work and Coade stone was exported around the world, everywhere from

Philadelphia to Poland. Eleanor opened a gallery to which the public were

admitted between 10am and 4pm for one shilling per person, so she even managed

to make money by charging people to see her work, let alone sell it – what a

businesswoman she was!

|

| Coade stone statue of George III, now in the grounds of Lincoln Castle. © Joanne Major |

Another example of her strong character was evident in 1774. She was annoyed that, as a result of a hard frost, a number of pieces made from artificial stone were damaged and so again took to the newspapers to make it crystal clear that such damaged pieces were an inferior product and not from her factory.

Eleanor Coade was a neighbour of the subject of our latest biography, A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs. Charlotte, as she preferred to be known, was the daughter of a Welshman who relocated to Lambeth when she was still a child. The Williams family took a house on Narrow Wall (where the Festival Hall complex is now situated) just a few doors away from Eleanor’s artificial stone manufactory. Eleanor Coade was probably aware of the gossip surrounding Charlotte’s torment in her late teens by a ‘libertine, half mad and half fool’, a man who owned one of the timber yards on the Lambeth shoreline and whose mother also lived on Narrow Wall.

If you’d like to discover more about Charlotte

and her Lambeth neighbours, all is revealed in A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams

Biggs which is out now in the UK (and coming soon

worldwide) and can be found at Pen & Sword, Amazon and all good bookshops.

Rachel

Charlotte Williams Biggs lived an incredible life, one which proved that fact

is often much stranger than fiction. As a young woman she endured a tortured

existence at the hands of a male tormentor, but emerged from that to reinvent

herself as a playwright and author; a political pamphleteer and a spy, working

for the British Government and later single-handedly organising George III’s

jubilee celebrations. Trapped in France during the revolutionary years of

1792-95, she published an anonymous account of her adventures. However, was

everything as it seemed? The extraordinary Mrs Biggs lived life upon her own

terms in an age when it was a man’s world, using politicians as her mouthpiece

in the Houses of Parliament and corresponding with the greatest men of the day.

Throughout it all though, she held on to the ideal of her one youthful true

love, a man who abandoned her to her fate and spent his entire adult life in

India. Who was this amazing lady?

In A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of

Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs, we delve into her life to reveal her

accomplishments and lay bare Mrs Biggs’ continued re-invention of herself. This

is the bizarre but true story of an astounding woman persevering in a man’s

world.

Sources

Used

Public Advertiser (London, England),

Wednesday, 11th September 1771

Coade’s Gallery, or, exhibition in

artificial stone, Westminster Bridge Road 1799

National Archives PROB 11/860/509

Tiverton Parish Registers

Sunday, 8 October 2017

Manchester's Coaching Days

|

| Pickford's Royal Fly-van. |

Even in central Manchester, the roads were so bad that no business person or well-to-do family kept their own carriage until Madame Drake, of Long Millgate, set up her carriage in 1758.

Turnpikes became a popular method of upgrading roads locally. The road to Stockport was probably the first in the Manchester area to be turnpiked, by the Manchester and Buxton Turnpike Trust in 1725. A quarter of a century later, however, a ‘flying coach’ still took four and a half days to reach London from Manchester.

|

| Last days of the Manchester Defiance. |

In 1760, Manchester got its first stagecoach service, when John Hanforth and his partners set up regular runs from London to Manchester and Liverpool to Manchester. Merchants and traders could now reach the capital in three days, ‘if God permit’. By the late 1770s, Pickford’s flying coach took two days to reach London.

And during Britain’s lengthy war with France, when news broke of the Peace of Amiens in 1802, the Defiance and Telegraph coaches brought the longed-for tidings from the capital to Manchester within twenty-four hours (usually the run took thirty hours).

But it was the Canal Age which put Manchester at the forefront of the transport revolution, as we shall see.

Monday, 14 August 2017

The Birth of Cottonopolis

|

| Manchester in the 1740s. |

By the early 1640s the area’s textile industries were firmly established. Cotton yarn (imported via Ireland) was woven with linen yarn made from flax to make sturdy ‘fustian’ cloth.

Families like the Chethams, Mosleys and Tippings became very wealthy buying and selling woollen cloths, linens, cotton yarn, and fustians. The wholesalers and master-manufacturers of Manchester became famous. As these ‘Manchester men’ became richer they built fine homes and large warehouses for their goods.

In the early 1700s pretty, light all-cotton calicoes imported from India and the East threatened to wipe out Britain’s woollen industry. An act of 1721 banned the wearing of, weaving or selling of any printed all-cotton ‘stuffs’ or ‘calicoes’ whether imported or made in Britain. However, ‘fustians’ were exempted, to protect Manchester’s workers. Woollen and worsted weavers petitioned parliament to ban fustians, too, but the ‘Manchester Act’ of 1736 upheld the exemption. All-cotton printed goods remained banned, however.

In the early 1700s pretty, light all-cotton calicoes imported from India and the East threatened to wipe out Britain’s woollen industry. An act of 1721 banned the wearing of, weaving or selling of any printed all-cotton ‘stuffs’ or ‘calicoes’ whether imported or made in Britain. However, ‘fustians’ were exempted, to protect Manchester’s workers. Woollen and worsted weavers petitioned parliament to ban fustians, too, but the ‘Manchester Act’ of 1736 upheld the exemption. All-cotton printed goods remained banned, however. |

| Handloom weaving. |

During the 1740s, Manchester merchants bought the warps and raw cotton and gave the materials to weavers who worked in their own homes aided by their families. The raw cotton was carded (the fibres were straightened to form a long, fluffy ‘roving’), the rovings were spun into yarn, the yarn was wound onto bobbins, and finally woven into cloth on a loom.

John Kay’s flying shuttle (1733) made hand-weaving easier. Then several key inventions speeded up first the spinning, then weaving of cotton. Lewis Paul and John Wyatt had the idea of thinning out cotton fibre using rollers, and James Hargreaves’s machine, the ‘spinning jenny,’ patented in 1770, revolutionised spinning.

|

| Hargreaves' spinning jenny at North Mill, Belper |

|

| Arkwright's water frame at North Mill, Belper. |

|

| Mule spinning room |

The big breakthrough for mechanized weaving came when Edmund Cartwright patented a powered loom in 1785. In a future blog post, I’ll look at how steam power affected Manchester during the industrial revolution.

Friday, 21 July 2017

Manchester and Salford Burials

|

| Monuments at St Ann's church, Manchester. |

It's very worthwhile joining the MLFHS as you will then have full access to their online databases.

Manchester City Council has a burial search facility for Blackley Crematorium, and Blackley, Gorton, Philips Park, Southern, and Manchester General cemeteries (fee payable to see the full details).

Sadly few grave monuments survive in Manchester city centre itself except for those outside St. Ann's church (above left).

The Lancashire OPC free website is also very useful for baptisms and burials in the area, and new transcriptions are being added all the time.

Church and chapel registers can also be accessed at Manchester Central Library, and details are available here.

Salford Local History Library has excellent local and family history collections, too.

Image (right): a receipt for grave 237, Salford Brough Cemetery, 23 September 1879 for Jos. Gartell( or Garlett?). Author's collection.

Friday, 23 June 2017

Fenian Fever

Today I'm very pleased to welcome fab author Angela Buckley to my blog! Angela has a new book out - a true-life Manchester murder mystery.

Fenian

Fever

By

Angela Buckley

|

| Smithfield Market. |

On 11 September 1867, a vigilant police

constable spotted two suspicious-looking men hanging around Smithfield Market

in central Manchester. The officer suspected them of planning to burgle a shop,

and when one of the men pulled out a gun, he arrested them. The prisoners, who

gave false names, were charged with loitering. During their detention,

communication between the police in Manchester and the Irish authorities

revealed the two men’s true identities: Colonel Thomas Kelly and Captain

Timothy Deasy of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who were wanted on suspicion

of terrorism. Both veterans of the American Civil War, they had come to England

to take part in actions against the British government to force the issue of

home rule.

A week later, the prisoners were to be

transferred to Belle Vue Gaol, at the edge of the city.

Travelling in a

horse-drawn Black Maria with other offenders, including women, Kelly and Deasy

were accompanied by Sergeant Charles Brett, who was locked inside the van with

them. Several more officers followed behind. As the convoy passed under a

bridge at Ardwick Green, a volley of stones hit the van forcing it to stop. The

police were then quickly surrounded by armed men, who shot both the horses and

wounded at least two officers. Unable to enter the locked Black Maria, the

assailants screamed through the ventilation slot for the keys, which were held

by Sergeant Brett. In a desperate attempt to protect the prisoners on board,

especially the women, the young police officer refused to hand over the keys. A

gunman poked his rifle through the slot and shot Sergeant Brett through the

head. The bullet passed through his skull and lodged in his helmet.

|

| Charles Brett's memorial. |

|

| 'Manchester Martyrs'. |

Once they were released, Colonel Kelly and

Captain Deasy fled the scene. Within three days of the incident, the police had

arrested some 50 Irish men, 26 of whom were charged. Later that year, on 25

November 1867, William Allen, Michael Larkin and Michael O’Brien were hanged

for Sergeant Brett’s murder - they became known as the ‘Manchester Martyrs’.

Following the death of Sergeant Brett, ‘Fenian fever’ had spread like wildfire

throughout Britain, causing the Victorians to fear the very real threat of

Irish nationalists and their deadly campaign. This deep-seated terror would

have a dramatic impact on three Irish brothers who also stood trial for murder

in Manchester, a decade later.

On 1 August 1876, PC Nicholas Cock was

walking his beat at midnight in the township of Chorlton-cum-Hardy, about four

miles from Manchester city centre. The young officer had stopped at the

junction of West Point, where three main thoroughfares converge, to chat with

one of his colleagues and a passing law student. The three men went their

separate ways and, a few minutes later, two shots rang out in the dark. PC James

Beanland and student John Massey Simpson ran back to the junction to find PC

Cock lying on the ground in a pool of blood - he had been shot. When Nicholas

Cock later died of his injuries, a manhunt began.

On hearing the terrible news, PC Cock’s

superior, Superintendent James Bent, knew instantly who the culprits were and

he arrested three local Irish labourers soon after. The Habron brothers had

crossed the path of PC Cock many times and he had been responsible for their

being charged with drunkenness on at least two occasions. Residents of Chorlton

had even overheard the brothers threatening to do away with PC Cock. Despite

the circumstantial nature of the evidence against them, which was based on boot

prints found near the scene of the crime, Superintendent Bent managed to secure

a conviction against the youngest brother William, aged 18, who received the

death sentence. It is likely that this was only possible due to the prejudice

towards the Irish community which was still prevalent at all levels of

Victorian society. The conviction was followed by a desperate race to spare

William Habron from the gallows. Three years later, a startling confession by a

notorious career criminal finally revealed the truth about who killed Constable

Cock.

Who Killed Constable Cock? by Angela Buckley is out now in ebook and

paperback. You can find out more about Angela’s work on her website, www.angelabuckleywriter.com and on her Facebook page Victorian Supersleuth.

Images

1. Smithfield Market, Manchester. Copyright free - from author’s collection.

2. The memorial to Sergeant Charles Brett, St Ann’s church, Manchester. © A Buckley.

3. Poster commemorating the Manchester Martyrs. Source: Wikicommons.

4. Memorial to the Manchester Martyrs at Moston Cemetery. Source: Wikicommons,

Wednesday, 21 June 2017

Town Hall Guest Post

|

| Manchester Town Hall |

Tuesday, 20 June 2017

Regency Manchester Guest Post

|

| From J. Aston's Picture of Manchester, 1826, courtesy Google Books. |

Friday, 9 June 2017

The Pentrich Rising, 1817

Hunger and distress were the prime movers behind the ill-fated Pentrich Rising. On the same night as the abortive Huddersfield rebellion, the White Horse pub in Pentrich was the ‘nerve centre’ of the planned rebellion. The pub was owned by Nanny Weightman, mother of George Weightman, one of the chief ‘delegates’ involved in the uprising.

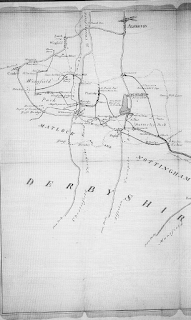

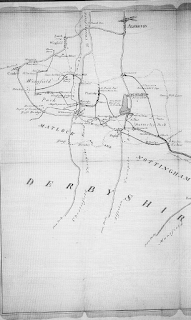

Jeremiah Brandreth, an out-of-work framework knitter known as the ‘Nottingham Captain’ and former Luddite, was now in charge of the rebellion (the ringleader, Tommy Bacon, was in hiding). Brandreth studied a map and pointed out the ‘line of march’ to his men. The rebels were to set off from South Wingfield at 10 pm, reach Pentrich by midnight, then ‘drive Butterley [the ironworks] before them’.

Jeremiah Brandreth, an out-of-work framework knitter known as the ‘Nottingham Captain’ and former Luddite, was now in charge of the rebellion (the ringleader, Tommy Bacon, was in hiding). Brandreth studied a map and pointed out the ‘line of march’ to his men. The rebels were to set off from South Wingfield at 10 pm, reach Pentrich by midnight, then ‘drive Butterley [the ironworks] before them’.

They planned to steal as many arms as possible, then march to Nottingham Forest and meet another large party of rebels. Brandreth said that Sheffield and Manchester would rise at the same time. This belief in simultaneous risings elsewhere had been actively fostered by the government's spies.

At the time appointed on Monday night (9 June), Jeremiah Brandreth, George Weightman and about sixty others, some with makeshift pikes, gathered at Hunt’s Barn in South Wingfield. Brandreth was armed with a gun and pistol; Weightman was armed, too.

The rebels divided into two ‘regiments’ to gather arms and recruits; Brandreth, Isaac Ludlam (armed with a spear) and ex-soldier William Turner were in the first group. They went to peoples’ houses, hammered on their doors and demanded weapons. The men of each household were asked to

‘volunteer’ to join them; they threatened to shoot those who refused.

Tragedy struck when Brandreth and his men reached the home of Mrs Hepworth, a widow living with her sons. They banged on her door, but Mrs Hepworth refused to open it. The men shouted at her son William, ‘We must have your guns and your men, or we will blow your brains out’. Someone (probably Brandreth) fired through the kitchen window, and the bullet hit servant Robert Walters in the neck. He died shortly afterwards.

The rebels, about 100 in number, next went to Butterley Ironworks and tried to get in. But the works had been barricaded against them, and they left empty-handed. Some of the insurgents began to drift away. Then cavalrymen were spotted in the distance – the 15th Hussars, commanded by Captain Phillips, had been sent to investigate. The remaining rebels threw down their weapons and ran for their lives.

The Pentrich rebellion was over.

Jeremiah Brandreth, William Turner and Isaac Ludlam were hanged for high treason at the Friar-Gate Gaol, Derby, on Friday 7 November 1817. Fourteen other rebels were transported for life. You can read genealogies of the families involved in the Pentrich Rising here.

Images: Maps showing the area of South Wingfield and Pentrich (HO42/166), and a letter from two Nottingham magistrates, Charles L Morley and J H Barber, with ‘informations’ on oath to Lord Sidmouth that they suspected Thomas Bacon, Jeremiah Brandreth, Samuel Haynes and others of ‘treasonable practices’(HO44/166/f.410).

Butterley Iron Works. Author's collection. Pictorial Gallery of Arts Vol. I, (c. 1860).

Jeremiah Brandreth, an out-of-work framework knitter known as the ‘Nottingham Captain’ and former Luddite, was now in charge of the rebellion (the ringleader, Tommy Bacon, was in hiding). Brandreth studied a map and pointed out the ‘line of march’ to his men. The rebels were to set off from South Wingfield at 10 pm, reach Pentrich by midnight, then ‘drive Butterley [the ironworks] before them’.

Jeremiah Brandreth, an out-of-work framework knitter known as the ‘Nottingham Captain’ and former Luddite, was now in charge of the rebellion (the ringleader, Tommy Bacon, was in hiding). Brandreth studied a map and pointed out the ‘line of march’ to his men. The rebels were to set off from South Wingfield at 10 pm, reach Pentrich by midnight, then ‘drive Butterley [the ironworks] before them’.They planned to steal as many arms as possible, then march to Nottingham Forest and meet another large party of rebels. Brandreth said that Sheffield and Manchester would rise at the same time. This belief in simultaneous risings elsewhere had been actively fostered by the government's spies.

At the time appointed on Monday night (9 June), Jeremiah Brandreth, George Weightman and about sixty others, some with makeshift pikes, gathered at Hunt’s Barn in South Wingfield. Brandreth was armed with a gun and pistol; Weightman was armed, too.

The rebels divided into two ‘regiments’ to gather arms and recruits; Brandreth, Isaac Ludlam (armed with a spear) and ex-soldier William Turner were in the first group. They went to peoples’ houses, hammered on their doors and demanded weapons. The men of each household were asked to

|

| Butterley Ironworks. |

Tragedy struck when Brandreth and his men reached the home of Mrs Hepworth, a widow living with her sons. They banged on her door, but Mrs Hepworth refused to open it. The men shouted at her son William, ‘We must have your guns and your men, or we will blow your brains out’. Someone (probably Brandreth) fired through the kitchen window, and the bullet hit servant Robert Walters in the neck. He died shortly afterwards.

The rebels, about 100 in number, next went to Butterley Ironworks and tried to get in. But the works had been barricaded against them, and they left empty-handed. Some of the insurgents began to drift away. Then cavalrymen were spotted in the distance – the 15th Hussars, commanded by Captain Phillips, had been sent to investigate. The remaining rebels threw down their weapons and ran for their lives.

|

| Letter re Brandreth and other rebels. |

The Pentrich rebellion was over.

Jeremiah Brandreth, William Turner and Isaac Ludlam were hanged for high treason at the Friar-Gate Gaol, Derby, on Friday 7 November 1817. Fourteen other rebels were transported for life. You can read genealogies of the families involved in the Pentrich Rising here.

Images: Maps showing the area of South Wingfield and Pentrich (HO42/166), and a letter from two Nottingham magistrates, Charles L Morley and J H Barber, with ‘informations’ on oath to Lord Sidmouth that they suspected Thomas Bacon, Jeremiah Brandreth, Samuel Haynes and others of ‘treasonable practices’(HO44/166/f.410).

Butterley Iron Works. Author's collection. Pictorial Gallery of Arts Vol. I, (c. 1860).

Thursday, 8 June 2017

Folly Hall Bridge: A Forgotten Uprising

|

| The old Luddite meeting place at Cooper Bridge. |

Thanks to their spies, the authorities now had the approximate date of the insurrection (9 June), the name of the main ringleader, ‘Old Tommy’ Bacon, and the names and addresses of those involved. The magistrates could have stepped in and made more arrests at any point, but they let events unfold unmolested. It’s difficult to escape the conclusion that the government was happy for the risings to go ahead to see how far the ringleaders were really prepared to go.

The rising in Yorkshire took place a day early (Sunday 8 June) because of a last-minute change of plan to rescue some would-be rebels recently arrested at Thornhill. The ‘revolution’ in the Huddersfield area broke out on with robberies as the men tried to get hold of arms.

Meanwhile, about 300–400 men assembled at Folly Hall Bridge (also known as Engine Bridge) about half a mile from Huddersfield along the road leading to Holmfirth and Honley. The men, armed with guns, pistols, and makeshift pikes, planned to march on Huddersfield when reinforcements arrived from the neighbouring villages. At midnight their leader, George Taylor, declared: ‘Now, my lads, all England is in arms – our liberties are secure – the rich will be poor, and the poor will be rich!’

About thirty minutes later the Huddersfield Yeomanry Cavalry, headed by Captain Armitage, went to reconnoitre the bridge, aided by the local constable, George Whitehead. As they approached the bridge, one man shouted ‘Who goes there?’ and aimed a gun at Whitehead. When Whitehead replied, the man took aim and fired, but it flashed in the pan.

After an exchange of fire, in which a cavalryman’s horse was wounded, the ‘Patrole found themselves compelled to retire to Huddersfield’ for reinforcements. When the soldiers returned, they found the rebels had already scattered and gone home. No-one else turned up to support the ‘revolution’; the Folly Hall Bridge rising was over.

But in Derbyshire, it was now time to ‘either fight or starve’, as we shall see tomorrow.

Thursday, 1 June 2017

Review of Tracing Your Manchester and Salford Ancestors

I'm thrilled to bits with this review of Tracing Your Manchester and Salford Ancestors in the July issue of WDYTYA magazine (which also contains my feature on researching framework knitters)! Many thanks to Ruth A Symes for her detailed review.

Wednesday, 17 May 2017

Was Your Ancestor A Peterloo Casualty?

|

| Peterloo print, courtesy Library of Congress. |

On this dreadful day in Manchester's long history, sixty to eighty thousand people - including women and children - had assembled at St Peter’s Field to attend a meeting on parliamentary reform, with Henry 'Orator' Hunt as the keynote speaker.

Although the meeting was peaceful, local magistrates, fearing that a riot was imminent, ordered yeomanry cavalry into the crowd to arrest Hunt.

The Manchester and Salford Yeomanry rode into the crowd, brandishing their sabres. But the people could not move to give them room.The horses panicked; the yeomanry lost their temper, and began hacking their way through. Over four hundred people were injured - many wounds were from sabre cuts - and between eleven and fifteen people died (accounts disagree).

|

| Plaque commemorating the Peterloo victims. |

The true number of casualties has never been completely ascertained. Many books have been written on Peterloo, including this one by Professor Michael Bush; my new book has some tips on researching Peterloo, too. There's also info and transcripts of contemporary documents here on the Peterloo Witness Project.

MLFHS is setting up a new website to discover people's family history stories which will go live on 1 June. If you are interested in contributing to this project, please visit the website when live, or contact the project manager Rod Melton by email at peterloo@mlfhs.org.uk.

Or if you are visiting Manchester Central Library after the project launches, Rod Melton will be available each Tuesday between 10:30 and 15:00. Please go to the Manchester and Lancashire Family History desk and ask for Rod and he will come down to see you.

The hope is to create a fitting and lasting memorial to all the victims of that fateful day.

Thursday, 27 April 2017

Manchester and Salford Ancestors Now Out On Kindle!

|

| Manchester Cathedral. |

If you are visiting Manchester Central Library, you can also buy it over the counter, which will save you paying postage. My book is also available on the Manchester and Lancashire Family History Society online bookshop.

Entries are now open for my Goodreads Giveaway, too, so do please have a go!

Wednesday, 19 April 2017

Win A Signed Copy of Tracing Your Manchester and Salford Ancestors!

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Tracing Your Manchester and Salford Ancestors

by Sue Wilkes

Giveaway ends May 30, 2017.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

Wednesday, 12 April 2017

Kings of Georgian Britain

Today I'm welcoming fab historian Catherine Curzon back to my blog! Her new book Kings of Georgian Britain is available now from Pen and Sword, Amazon UK and Amazon US.

Over to you, Catherine!

A Family in Mourning

There is much to be said for a loving home and a warm hearth and for King George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, family life was an anchor in stormy waters. As war raged in America, debate raged in Parliament and his eldest sons raged to whoever would listen, George took refuge in the gentle comfort of his wife and their growing brood of children.

As parents to fourteen children, the royal couple knew that they had been fortunate in not yet having lost any of their offspring. They were devoted parents who always made time for play, yet real life was about to force its way brutally into this happy idyll. In the space of less than twelve short months, those loving parents would lose not one child, but two.

In the eighteenth century, smallpox was a very real and present threat to the lives of all, whether prince or pauper. The disease claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and those who survived were often left with devastating side effects that ranged from disfiguring scars to total blindness. For any parent, the news that their child had been infected would be terrifying and inoculation was growing in popularity, despite its risks.

In 1782, George and Charlotte took the decision to have their youngest children inoculated against

smallpox and by June, they no doubt rued that day. Little Alfred, the couple’s youngest son, younger than his oldest brother, fell ill not long after receiving the treatment. In order to speed his recovery, he was taken to enjoy the sea air at Deal in the care of Lady Charlotte Finch, the household’s trusted nurse.

A cheery little boy with a bright disposition, Alfred was nevertheless laid low by his inoculation and began to experience smallpox-like blemishes on his face, whilst his breathing grew ever more laboured. Only when it appeared that the seaside was not working its magic was he returned to Windsor. Here he was attended by court physicians and their conclusion, when it came, was devastating. Little Alfred would be dead within weeks.

“Yesterday morning died at the Royal Palace, Windsor, his Royal Highness Prince Alfred, their Majesties youngest son. The Queen is much affected at this domestic calamity, probably more so on account of its being the only one she has experienced after a marriage of 20 years and having been the mother of fourteen children.” (London Chronicle, August 20, 1782 – August 22, 1782; issue 4014, p.1.)

Prince Alfred of Great Britain passed away on 20th August 1782, just a month shy of his second birthday, and the royal family was rocked by his death. He was buried at Westminster Abbey with full honours and though George and Charlotte mourned his loss, they took comfort in their surviving children. The king, in particular, doted on the boy who was now his youngest son, three-year old Octavius. In his darkest moments he admitted that, should Octavius have died, then he would wish himself dead too.

These were to be fateful words.

Despite Alfred’s death, it was still reckoned that inoculating the children against smallpox posed less of a risk than leaving them open to the infection so Octavius and his sister, five-year-old Princess Sophia, were given the treatment. Whilst Sophia suffered no ill effects, things did not go so well for Octavius.

The queen was pregnant with her final child when, just days after receiving the inoculation, Octavius fell ill. Unlike Alfred, whose sickness progressed over time, Octavius declined with alarming speed and died on 3rd May 1783. The king was beyond devastated, tormented to distraction by grief and lower than he had ever been.

“On Saturday, on the Majesties arriving at Kew, in their way to Windsor, and finding Prince Octavius in a dangerous Way, they determined to stay there all Night and sent an Express to Windsor to acquaint the Attendants of the Reason of their continuing there. The same Night died at Kew, his Royal Highness Prince Octavius, his Majesty’s youngest Son, in the fifth Year of his Age.” (Daily Advertiser, Monday, May 5, 1783; issue 17249, p.1.)

The king brooded on the loss of his children, convinced that their inoculation against smallpox had contributed to their early deaths. Where once there had been the laughter of infants, the gentle distraction offered when Charlotte and George played adoringly with the youngsters, now there was only silence and grief, the royal household plunged into sadness. A little respite came with the birth of Princess Amelia in August of that same year and George showered her with love, filling the void where his sons had been with the cheer of this new daughter. Little Amelia, or Emily, as she was known, lived through childhood but years later it would be her death that was to have a catastrophic effect on the father who adored her.

Bibliography

Anonymous. An Historical Account of the Life and Reign of King George the Fourth. London: G Smeeton, 1830.

Anonymous. George III: His Court and Family, Vol I. London: Henry Colburn and Co, 1821.

Aspinall, Arthur. The Later Correspondence of George III.: December 1783 to January 1793, Vol II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Aspinall, Arthur. Letters of the Princess Charlotte 1811–1817. London: Home and Van Thal, 1949.

Baker, Kenneth. George III: A Life in Caricature. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Black, Jeremy. George III: America’s Last King. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Black, Jeremy. The Hanoverians: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon and London, 2007. Burney, Frances. The Diary and Letters of Frances Burney, Madame D’Arblay, Vol II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1910.

Craig, William Marshall. Memoir of Her Majesty Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz, Queen of Great Britain. Liverpool: Henry Fisher, 1818.

Hadlow, Janice. The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians. London: William Collins, 2014.

Hibbert, Christopher. George III: A Personal History. London: Viking, 1998.

Tillyard, Stella. A Royal Affair: George III and his Troublesome Siblings. London: Vintage, 2007.

Author Biography

Catherine Curzon is a royal historian who writes on all matters 18th century at www.madamegilflurt.com. Her work has been featured on HistoryExtra.com, the official website of BBC History Magazine and in publications such as Explore History, All About History, History of Royals and Jane Austen’s Regency World. She has provided additional research for An Evening with Jane Austen at the V&A and spoken at venues including the Royal Pavilion in Brighton,

Lichfield Guildhall, the National Maritime Museum and Dr Johnson’s House.

Catherine holds a Master’s degree in Film and when not dodging the furies of the guillotine, she lives in Yorkshire atop a ludicrously steep hill.

Social media

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Madame-Gilflurt/583720364984695?ref=br_rs

https://twitter.com/madamegilflurt

https://plus.google.com/+MadameGilflurt

https://uk.pinterest.com/madamegilflurt/

https://www.instagram.com/catherinecurzon/

About the Book

For over a century of turmoil, upheaval and scandal, Great Britain was a Georgian land.

From the day the German-speaking George I stepped off the boat from Hanover, to the night that George IV, bloated and diseased, breathed his last at Windsor, the four kings presided over a changing nation.

Kings of Georgian Britain offers a fresh perspective on the lives of the four Georges and the events that shaped their characters and reigns. From love affairs to family feuds, political wrangling and beyond, peer behind the pomp and follow these iconic figures from cradle to grave. After all, being

a king isn’t always grand parties and jaw-dropping jewels, and sometimes following in a father’s footsteps can be the hardest job around.

Take a trip back in time to meet the wives, mistresses, friends and foes of the men who shaped the nation, and find out what really went on behind closed palace doors. Whether dodging assassins, marrying for money, digging up their ancestors or sparking domestic disputes that echoed down the generations, the kings of Georgian Britain were never short on drama.

Over to you, Catherine!

A Family in Mourning

There is much to be said for a loving home and a warm hearth and for King George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, family life was an anchor in stormy waters. As war raged in America, debate raged in Parliament and his eldest sons raged to whoever would listen, George took refuge in the gentle comfort of his wife and their growing brood of children.

As parents to fourteen children, the royal couple knew that they had been fortunate in not yet having lost any of their offspring. They were devoted parents who always made time for play, yet real life was about to force its way brutally into this happy idyll. In the space of less than twelve short months, those loving parents would lose not one child, but two.

In the eighteenth century, smallpox was a very real and present threat to the lives of all, whether prince or pauper. The disease claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and those who survived were often left with devastating side effects that ranged from disfiguring scars to total blindness. For any parent, the news that their child had been infected would be terrifying and inoculation was growing in popularity, despite its risks.

In 1782, George and Charlotte took the decision to have their youngest children inoculated against

smallpox and by June, they no doubt rued that day. Little Alfred, the couple’s youngest son, younger than his oldest brother, fell ill not long after receiving the treatment. In order to speed his recovery, he was taken to enjoy the sea air at Deal in the care of Lady Charlotte Finch, the household’s trusted nurse.

A cheery little boy with a bright disposition, Alfred was nevertheless laid low by his inoculation and began to experience smallpox-like blemishes on his face, whilst his breathing grew ever more laboured. Only when it appeared that the seaside was not working its magic was he returned to Windsor. Here he was attended by court physicians and their conclusion, when it came, was devastating. Little Alfred would be dead within weeks.

“Yesterday morning died at the Royal Palace, Windsor, his Royal Highness Prince Alfred, their Majesties youngest son. The Queen is much affected at this domestic calamity, probably more so on account of its being the only one she has experienced after a marriage of 20 years and having been the mother of fourteen children.” (London Chronicle, August 20, 1782 – August 22, 1782; issue 4014, p.1.)

Prince Alfred of Great Britain passed away on 20th August 1782, just a month shy of his second birthday, and the royal family was rocked by his death. He was buried at Westminster Abbey with full honours and though George and Charlotte mourned his loss, they took comfort in their surviving children. The king, in particular, doted on the boy who was now his youngest son, three-year old Octavius. In his darkest moments he admitted that, should Octavius have died, then he would wish himself dead too.

These were to be fateful words.

Despite Alfred’s death, it was still reckoned that inoculating the children against smallpox posed less of a risk than leaving them open to the infection so Octavius and his sister, five-year-old Princess Sophia, were given the treatment. Whilst Sophia suffered no ill effects, things did not go so well for Octavius.

The queen was pregnant with her final child when, just days after receiving the inoculation, Octavius fell ill. Unlike Alfred, whose sickness progressed over time, Octavius declined with alarming speed and died on 3rd May 1783. The king was beyond devastated, tormented to distraction by grief and lower than he had ever been.

“On Saturday, on the Majesties arriving at Kew, in their way to Windsor, and finding Prince Octavius in a dangerous Way, they determined to stay there all Night and sent an Express to Windsor to acquaint the Attendants of the Reason of their continuing there. The same Night died at Kew, his Royal Highness Prince Octavius, his Majesty’s youngest Son, in the fifth Year of his Age.” (Daily Advertiser, Monday, May 5, 1783; issue 17249, p.1.)

The king brooded on the loss of his children, convinced that their inoculation against smallpox had contributed to their early deaths. Where once there had been the laughter of infants, the gentle distraction offered when Charlotte and George played adoringly with the youngsters, now there was only silence and grief, the royal household plunged into sadness. A little respite came with the birth of Princess Amelia in August of that same year and George showered her with love, filling the void where his sons had been with the cheer of this new daughter. Little Amelia, or Emily, as she was known, lived through childhood but years later it would be her death that was to have a catastrophic effect on the father who adored her.

Bibliography

Anonymous. An Historical Account of the Life and Reign of King George the Fourth. London: G Smeeton, 1830.

Anonymous. George III: His Court and Family, Vol I. London: Henry Colburn and Co, 1821.

Aspinall, Arthur. The Later Correspondence of George III.: December 1783 to January 1793, Vol II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Aspinall, Arthur. Letters of the Princess Charlotte 1811–1817. London: Home and Van Thal, 1949.

Baker, Kenneth. George III: A Life in Caricature. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Black, Jeremy. George III: America’s Last King. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Black, Jeremy. The Hanoverians: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon and London, 2007. Burney, Frances. The Diary and Letters of Frances Burney, Madame D’Arblay, Vol II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1910.

Craig, William Marshall. Memoir of Her Majesty Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz, Queen of Great Britain. Liverpool: Henry Fisher, 1818.

Hadlow, Janice. The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians. London: William Collins, 2014.

Hibbert, Christopher. George III: A Personal History. London: Viking, 1998.

Tillyard, Stella. A Royal Affair: George III and his Troublesome Siblings. London: Vintage, 2007.

Author Biography

Catherine Curzon is a royal historian who writes on all matters 18th century at www.madamegilflurt.com. Her work has been featured on HistoryExtra.com, the official website of BBC History Magazine and in publications such as Explore History, All About History, History of Royals and Jane Austen’s Regency World. She has provided additional research for An Evening with Jane Austen at the V&A and spoken at venues including the Royal Pavilion in Brighton,

Lichfield Guildhall, the National Maritime Museum and Dr Johnson’s House.

Catherine holds a Master’s degree in Film and when not dodging the furies of the guillotine, she lives in Yorkshire atop a ludicrously steep hill.

Social media

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Madame-Gilflurt/583720364984695?ref=br_rs

https://twitter.com/madamegilflurt

https://plus.google.com/+MadameGilflurt

https://uk.pinterest.com/madamegilflurt/

https://www.instagram.com/catherinecurzon/

About the Book

For over a century of turmoil, upheaval and scandal, Great Britain was a Georgian land.

From the day the German-speaking George I stepped off the boat from Hanover, to the night that George IV, bloated and diseased, breathed his last at Windsor, the four kings presided over a changing nation.

Kings of Georgian Britain offers a fresh perspective on the lives of the four Georges and the events that shaped their characters and reigns. From love affairs to family feuds, political wrangling and beyond, peer behind the pomp and follow these iconic figures from cradle to grave. After all, being

a king isn’t always grand parties and jaw-dropping jewels, and sometimes following in a father’s footsteps can be the hardest job around.

Take a trip back in time to meet the wives, mistresses, friends and foes of the men who shaped the nation, and find out what really went on behind closed palace doors. Whether dodging assassins, marrying for money, digging up their ancestors or sparking domestic disputes that echoed down the generations, the kings of Georgian Britain were never short on drama.

Thursday, 6 April 2017

New Release: Tracing Your Manchester and Salford Ancestors

I'm thrilled to announce that Tracing Your Manchester and Salford Ancestors has been released early! It's currently on special offer here on the Pen & Sword website, and should soon be in stock on Amazon.

Here's the blurb:

'For readers with family ties to Manchester and Salford, and researchers delving into the rich history of these cities, this informative, accessible guide will be essential reading and a fascinating source of reference.

Sue Wilkes outlines the social and family history of the region in a series of concise chapters. She discusses the origins of its religious and civic institutions, transport systems and major industries. Important local firms and families are used to illustrate aspects of local heritage, and each section directs the reader towards appropriate resources for their research. No previous knowledge of genealogy is assumed and in-depth reading on particular topics is recommended. The focus is on records relating to Manchester and Salford, including current districts and townships, and sources for religious and ethnic minorities are covered. A directory of the relevant archives, libraries, academic repositories, databases, societies, websites and places to visit, is a key feature of this practical book'.

|

| Suffragist Lydia E. Becker. |

Here's the blurb:

'For readers with family ties to Manchester and Salford, and researchers delving into the rich history of these cities, this informative, accessible guide will be essential reading and a fascinating source of reference.

Sue Wilkes outlines the social and family history of the region in a series of concise chapters. She discusses the origins of its religious and civic institutions, transport systems and major industries. Important local firms and families are used to illustrate aspects of local heritage, and each section directs the reader towards appropriate resources for their research. No previous knowledge of genealogy is assumed and in-depth reading on particular topics is recommended. The focus is on records relating to Manchester and Salford, including current districts and townships, and sources for religious and ethnic minorities are covered. A directory of the relevant archives, libraries, academic repositories, databases, societies, websites and places to visit, is a key feature of this practical book'.

|

| Salford hero Mark Addy. |

Tomorrow, I'm visiting the WDYTYA Live! show at the NEC, and if all goes to plan, I'll be signing copies of my new book at the Pen & Sword stand. Hope to see you there!

Monday, 20 March 2017

84 Plymouth Grove, Manchester

|

| 84 Plymouth Grove. |

In this house (no. 42 in Gaskell's lifetime) Elizabeth wrote Cranford, Ruth, North and South, The Life of Charlotte Bronte, and her last, unfinished work, Wives and Daughters.

(Mary Barton was written at one of the Gaskells' previous houses, 121 Upper Rumford St in Manchester).

|

| Family portraits and heirlooms. |

Elizabeth grew to love her new home; there was plenty of room for family and friends, and it had a large garden for her children to play in.

William had his own study for his writing and pastoral work; Elizabeth often wrote at a round desk in the dining room.

After Elizabeth's sudden death in 1865, her husband William and unmarried daughters Meta and Julia stayed in the house. The two sisters were well known locally for their charity work.

|

| Elizabeth's wedding veil. |

The house has been restored and furnished in a similar fashion to how the Gaskells would have known it; you can also see some family heirlooms, including Elizabeth's wedding veil, which was worn by her daughter Marianne on her own wedding day.

You have to pay for admission, but your ticket lasts for 12 months, so don't lose it! It was a cold, wet day when I visited, but it would be nice to explore the garden again in the summer.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)