The January/February 2025 issue of Jane Austen's Regency World has two features by me, on two very different subjects.

The first feature is on the tragic life and career of the author Charles Lamb.

The first feature is on the tragic life and career of the author Charles Lamb.

Charles Lamb was well known for his comic essays; but his life was marked by deep personal tragedy.

Very sadly, the Lamb family suffered from mental illness, especially his sister Mary.

Charles's life was changed forever after Mary, while very distressed, fatally stabbed their mother.

Nevertheless, Lamb steadily forged a writing career, publishing plays, novels, poems, and essays (under the sobriquet Elia). He also collaborated with Mary on their Tales from Shakespeare (1807), which is still in print today.

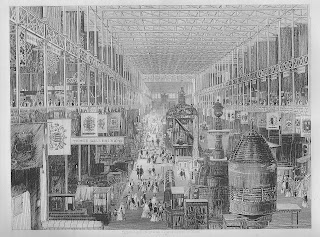

My other feature, part of my continuing series on the industrial revolution, is on the advent of railway engines, including Richard Trevithick's ground-breaking 'Catch-Me-Who-Can', and his 'tram-engine' (1804) which hauled minerals at Pen-y-Darren ironworks, South Wales.

Images from author's collection:

Top left: ‘Charles Lamb and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’. Illustration by Archibald Standish Hartrick (1864–1950), The Letters of Charles Lamb, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd, London, c.1903.

Image centre right: Interior of the Bell at Edmonton, from a sketch by J. White. A friend from the country had called upon Lamb.

Bottom. Exterior of the Bell at Edmonton, in Charles Lamb’s time. W. Carew Hazlitt, Mary and Charles Lamb: Poems, Letters and Remains, Chatto & Windus, London, 1874.

Image Left: Trevithick's High Pressure Tram-Engine, The Engineer’s and Mechanic’s Encyclopedia, Vol. II, Thomas Kelly, London, 1836.