|

| Hugh Thomson illustration for the Graphic, 1889. |

I'm an author specialising in family history, social history, industrial history and literary biography. Real stories; real people; real lives.

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 22 December 2015

Happy Christmas Everyone!

Thursday, 10 December 2015

The Spies

|

| 'Presentation of colours' to the militia. |

It spent thousands of pounds annually paying its own spies, and reimbursing local magistrates for their spies.

What kind of person was recruited as a spy? In London, the famous Bow Street Runners often undertook intelligence-gathering. In the provinces, lawyers were sometimes pressed into service (some notorious spies like Leonard McNally in Ireland, which rebelled in 1798, were legal professionals).

|

| Thomas Reynolds - a United Irish spy. |

Army

and navy officers and militia-men were also asked, or volunteered to,

infiltrate the meetings of Radicals, workers’ societies and revolutionary groups, and root out potential traitors on the home front.

In the industrial districts, some impoverished workers were only too happy to earn

good money informing on their neighbours.

This period was very profitable for the

Regency spies, but their lives were at risk if people realized they were being

betrayed. On

Saturday 9 May 1812, a Lancashire militia-man and his sweetheart died in

sinister circumstances. Sergeant John

Moore of the 1st Manchester Local Militia and his cousin Margaret were thrown

into the Rochdale Canal, near Manchester, where they drowned. A Manchester spy,

John Bent, later confirmed to the authorities that the locals had discovered

that Moore ‘was an informer’.

Wednesday, 2 December 2015

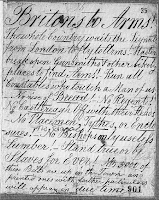

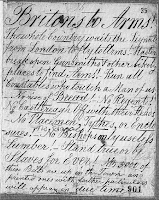

Britons To Arms! Spa Fields 1816.

|

| Spa Fields Chapel in the 1780s. |

|

| Spence's Plan. HO40/9, 1817. |

After Spence's death in 1814, a new society was set up by his adherents, which included former LCS members Thomas Evans and his son Thomas, who were earning a living as brace-makers in the Strand.

The

Spenceans held weekly meetings at pubs in the metropolis. Their members included Dr James Watson, ‘a respectable

surgeon and apothecary’, his son Jem or 'Young Watson', John Hooper, Thomas Preston – and Arthur Thistlewood, a brooding, dangerous

man.

In the autumn of 1816, the Spenceans wrote to Radical orator Henry Hunt, asking him to address a meeting at Spa Fields. Hunt, a very popular speaker, was sure to draw a large crowd. The Spenceans could use the meeting to test public support for their plans to overthrow the government.

|

| Hooper and Thistlewood. |

Shortly

before the meeting, 5,000 handbills were distributed in

London: 'Britons To Arms! The

whole country waits the Signal  from

London to fly to Arms! Hasten break

open Gunsmiths and other likely places

to find Arms!...

Stand True or be Slaves

for Ever!' (HO 40/3/3, f.901, 1816).

from

London to fly to Arms! Hasten break

open Gunsmiths and other likely places

to find Arms!...

Stand True or be Slaves

for Ever!' (HO 40/3/3, f.901, 1816).

from

London to fly to Arms! Hasten break

open Gunsmiths and other likely places

to find Arms!...

Stand True or be Slaves

for Ever!' (HO 40/3/3, f.901, 1816).

from

London to fly to Arms! Hasten break

open Gunsmiths and other likely places

to find Arms!...

Stand True or be Slaves

for Ever!' (HO 40/3/3, f.901, 1816).

Although this meeting passed off peacefully, the next one, on 2 December, was a very different affair. The government's spies reported that the Spenceans planned to attack the Bank of England and and the Tower of London (very similar to the Despard plot).

So on the appointed day, troops and police were out

in force in London. Dr Watson’s son Jem was first to address

the crowd. He climbed on a coal-waggon decorated with tri-coloured

flags: the emblem of the French revolution.

So on the appointed day, troops and police were out

in force in London. Dr Watson’s son Jem was first to address

the crowd. He climbed on a coal-waggon decorated with tri-coloured

flags: the emblem of the French revolution. When Hunt turned up at 1pm to address the 10,000-strong crowd, Young Watson was already heading towards Smithfield with several

hundred men. Jem shot a customer, Mr Platt, while raiding a gunsmith’s shop. Several shops were attacked, and a mob rampaged through the streets until stopped by the troops and cavalry.The Spenceans were now wanted men...

|

| The Home Office received regular updates as the riot was taking place. HO40/10. |

|

| Tricoloured flags. |

Monday, 23 November 2015

The Spymasters II

During the age of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Home Office wanted good, reliable intelligence on the domestic front as well as in the sphere of war. Persons of interest to the authorities included the government's political opponents and critics, disaffected Englishmen, Irish and Scots, and even workers agitating for better wages and working conditions.

If the government believed that trouble was brewing, it was a far

better use of resources to ensure that troops were already in place before they

were needed, and this is one of the reasons why spies were needed. Whitehall

relied heavily on reports from local magistrates and concerned loyalists for

news of potential troublemakers in the provinces.

|

| Many local JPs were active intelligence-gatherers. |

Unfortunately many local justices seem to have been particularly

pusillanimous and communicated every minor happenstance. Letters poured into

the Home Office on a daily basis, and the clerks had the unenviable task of

winnowing the chaff to determine which letters and spy reports were important

and required immediate action, and which were trivial.

Several local officials employed spies and informers to gather

information, which they forwarded to London. For example, magistrates like Col.Ralph Fletcher in Bolton, Rev. William R. Hay in Manchester, and clerk of the

peace John Lloyd of Stockport, were highly active correspondents. Their spies

and informers were given code-names in correspondence, such as ‘B’ or ‘S’;

sometimes the term ‘confidential agent’ or ‘confidential person’ was used.

Images:

John Bull fighting the French single-handed. Unknown artist, c. 1800.

Courtesy Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-10749.

'The Bench'. Hugh Thomson illustration for Our Village, Macmillan &

Co., 1893.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)