|

| Seamen complain about their rations. |

First of all, apologies for the radio silence! My

poor blogs have been much neglected over the last few weeks, as I've been very

busy writing a new book, but hopefully I should have more time to spend on them

now.

On 16 April 1797 the crews of the Royal Navy’s ships

at Spithead, including the Queen

Charlotte and Royal George, went

on strike. They refused to put to sea as ordered until their pay was raised,

and red flags of mutiny were run up the flagpoles.

The mutiny could not have come at a worse time, as a

French invasion was expected at any time (there was a landing at Fishguard

earlier that year). But the men had had enough. Living conditions in the fleet

were dreadful; crews were poorly paid, and their food and drink scarcely fit

for human consumption. Many sailors were ‘pressed’ men, and a brutal system of

floggings was used to enforce discipline.

The mutineers were primarily concerned with

improving their pay and conditions, rather than disloyalty to Britain. Great

care was taken to maintain discipline. Each ship had its own central committee;

another committee comprised two delegates from each disaffected ship. The men

took an oath of allegiance to one another.

|

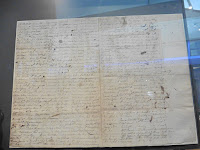

| Apology from the crew of the Mars. |

The strength of feeling amongst the men was so solid

that parliament agreed to several of the men’s demands. They were given a

substantial pay rise and offered a free pardon. By 23 April the mutiny appeared

over, but trouble began agains when doubts surfaced over whether the promised

pay rise would materialize. On 7 May the men of the London at

Spithead mutinied and three officers were imprisoned; soon more ships mutinied

at St Helens (a harbour on the Isle of Wight). The men were reassured by the

Admiralty, and returned to their duties.

|

| Richard Parker, mutineer. |

Meanwhile on 12 May another mutiny broke out at the Nore (Sheerness), led by Richard Parker, a well-educated seaman from Exeter,

who served on the Sandwich. The Nore

mutineers wanted better wages, like the Spithead men, and additional demands

such as a fairer distribution of prize-money (given when an enemy ship was

taken). When news reached the Nore of the terms agreed at Spithead, the

Admiralty believed that the men would back down.

But the Admiralty refused to give the extra

concessions which the Nore mutineers wanted, so the seamen seized some gunboats

in Sheerness harbour and fired at the fort there. Effigies of William Pitt and

Lord Dundas were hanged at the yard-arm. The language used by many ships’

delegates was clearly modelled on Thomas Paine's works. The men talked of their

rights and liberties, and the mutinous ships were dubbed the ‘Floating

Republic’.

In late May, some ships from Admiral Duncan’s fleet

joined the mutiny at the Nore instead of going to the Texel to blockade the

French as ordered. This action in wartime greatly shocked public opinion, and

lost the men much support.

During the first and second weeks of June, more and

more ships slipped away from the rebel fleet and surrendered. By 14 June the

mutiny was a spent force. Retribution was swift: Richard Parker and over twenty ringleaders were

hanged at the yard-arm. You can watch a YouTube video about the mutinies here.

Images:

Seamen complain about their rations prior to the mutiny

at the Nore. Cassell’s Illustrated History of England Vol. VI, (Cassell, Petter

and Galpin, c.1864). Author’s collection.

Letter dated 25 June 1797 from the sailors on board

the Mars, a 74-gunner, apologizing

for the mutiny. On display at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (MKH/15.4).

A 1797 etching of Richard Parker, leader of the mutineers

on the Nore. On display at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (PAH5441).