Every November, we commemorate the discovery in 1605 of

Guy Fawkes' Gunpowder Plot to blow up Parliament, over four hundred years after the event. Yet the Cato Street Conspirators - who planned to murder the whole British Cabinet and launch a revolution - are seemingly almost forgotten, even though it's the

bicentenary of their executions this year. Most of the plotters were arrested in a loft at

Cato Street following a

police 'sting' operation set up by Home Office

spy George Edwards.

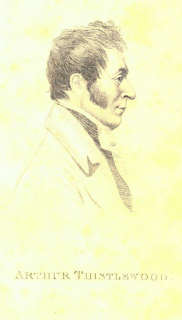

On Monday 1 May 1820, Arthur Thistlewood, James Ings, John Thomas Brunt, Richard Tidd and William Davidson were hanged for high treason before a vast crowd at Newgate prison.

What type of men were the

conspirators?

All the plotters were as poor as church mice. Their ringleader, Arthur Thistlewood, was already well known to the authorities for his role in the

Spa Fields Riots (December 1816). He was 5ft 8in high, with ‘a sallow complexion’, dark hair, ‘dark hazel eyes and arched eyebrows’, a wide mouth and good teeth. Arthur had a scar under his chin, and the ‘appearance of a military man’. He customarily wore a blue riding coat and blue pantaloons. Thistlewood, now about 25 years old, was on his second marriage, and had previously been unfortunate in his finances. Arthur had a pathological hatred of government ministers like Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth, and was notorious for his violent language and demeanour. When the police trap was sprung, Thistlewood fought his way out of the loft, killing a policeman, Smithers, with his sword. George Edwards later led the police to Thistlewood's hiding place.

James Ings, a Hampshire man, had formerly known more prosperous times, but lost much of his property and money during the trade slump after Waterloo. He had a wife, Celia, three daughters, and a son called William. Ings had recently kept a coffee-shop in Whitechapel, from which he sold political pamphlets, but this venture, too, failed. He was penniless in the run-up to the conspiracy, and is said to have been given money by government spy

George Edwards to rent a room which served as an arms depot for the conspirators.

John Thomas Brunt was lodging in the same house. A Londoner, he earned a living as a 'boot-closer', and was said to be an 'excellent workman'. A married man, in his late thirties, he had a fourteen-year-old son. Brunt was seemingly of a poetic turn. The night before his execution, he sent his wife the last shilling he possessed, begging her to 'keep the shilling for his sake for as long as she lived'.

He also wrote some verses for his wife:

Tho' in a cell I'm close confin'd,

No fears alarm the noble mind,

Tho' death itself appears in view,

Daunts not the soul sincerely true,

Cajole and plot their dark intrigues;

Still each Briton's last words shall be,

Oh! give me death or liberty!

(George Theodore Wilkinson,

An Authentic History of the Cato Street Conspiracy, London, 1820).

Richard Tidd, born in Grantham, was a Radical shoemaker alleged to have been involved in the

Despard conspiracy. Tidd was married, with a daughter, and lived in great poverty in Hole-in-the-Wall Passage, Baldwin's Gardens. It's said that Tidd fired a gun at a peace officer during the conspirators' arrest on 23 February.

William Davidson, 'a man of colour', was highly intelligent. Born in Kingston, Jamaica (where his father was Attorney-General), he came to England while still very young for a good education. He studied mathematics, and the law (for a time) before learning the trade of a cabinet-maker.

The

Authentic History of the Cato Street Conspiracy gives Davidson a very bad character, accusing him not only of an 'indelicate attack' on a Sunday School teacher, but also the young ladies who attended the school. He too was extremely poor following the failure of his business.

Several of the conspirators who were arrested were lucky to escape the gallows. Five others were transported to Australia.

Two more, John Monument and Thomas Adams turned King's evidence to save their skins.

Thomas Hiden, who had a last-minute change of heart and alerted the authorities to the plot (which they already knew about), was later rewarded with a job by the government.

However, Thistlewood also had links with other revolutionary groups in the UK, and the full extent of the conspiracy may never be fully known.