Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to all my readers! I hope you all have a peaceful Christmas with friends and family.

Image from the author's collection: 'The Ass'. The Affectionate Parent's Gift, and Good Child's Reward, T.Kelly, 1827

I'm an author specialising in family history, social history, industrial history and literary biography. Real stories; real people; real lives.

Saturday, 20 December 2014

Tuesday, 16 December 2014

Thursday, 4 December 2014

'Doing Their Bit'

In some earlier blog posts, I've looked at the sacrifices my family made during WW1. While soldiers were away fighting the war, the women and children of Britain 'did their bit' for the war effort, too, and this was true in both world wars. Women took over many jobs traditionally done by men before that date - working on the railways and buses, and in munitions factories and the steelworks.

Boys and girls - Scouts and Guides - helped with war work such as running messages, or harvesting crops. Young lads served in the navy and mercantile marine, and many patriotic underage teenage lads wangled their way onto active service. My book Tracing Your Ancestor's Childhood has lots of info on how to find out about records for your ancestors' wartime service and in youth organizations, and my latest feature for Family Tree looks at the effect of both world wars on children, especially at Christmastime.

Boys and girls - Scouts and Guides - helped with war work such as running messages, or harvesting crops. Young lads served in the navy and mercantile marine, and many patriotic underage teenage lads wangled their way onto active service. My book Tracing Your Ancestor's Childhood has lots of info on how to find out about records for your ancestors' wartime service and in youth organizations, and my latest feature for Family Tree looks at the effect of both world wars on children, especially at Christmastime.

Boys and girls - Scouts and Guides - helped with war work such as running messages, or harvesting crops. Young lads served in the navy and mercantile marine, and many patriotic underage teenage lads wangled their way onto active service. My book Tracing Your Ancestor's Childhood has lots of info on how to find out about records for your ancestors' wartime service and in youth organizations, and my latest feature for Family Tree looks at the effect of both world wars on children, especially at Christmastime.

Boys and girls - Scouts and Guides - helped with war work such as running messages, or harvesting crops. Young lads served in the navy and mercantile marine, and many patriotic underage teenage lads wangled their way onto active service. My book Tracing Your Ancestor's Childhood has lots of info on how to find out about records for your ancestors' wartime service and in youth organizations, and my latest feature for Family Tree looks at the effect of both world wars on children, especially at Christmastime.

Images

of women bus and tram conductors, and a mother and child hauling a canal boat along the Regent's Canal, from the Nigel Wilkes Collection: The

Times History of the War, Vol. IV, 1915.

Monday, 1 December 2014

Austenprose Review of A Visitor's Guide To Jane Austen's England!

A wonderful review of my new book A Visitor's Guide To Jane Austen's England is now live on the Austenprose website. Laurel Ann's site is a treasure trove of info about all things Austen-related, so have fun exploring it!

Tuesday, 25 November 2014

Birmingham Brass Founders

Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is a wonder material.

It’s highly malleable, does not rust when exposed to air, takes a high polish, and

lcan be cast into any shape. Birmingham artisans made cutlery and iron tools

since at least Tudor times, and in the 18th century the city was famous

for its metal ‘toys’ (buttons, buckles, etc.). Matthew Boulton of Soho was a

toy-manufacturer.

|

| Brass casting. |

Brass manufacture is said to have been introduced to Birmingham in 1740 by a Mr Turner, on Coleshill St. The growth of the city’s famous canal

network made it easy to transport raw materials and finished goods. By the mid-19th

century Birmingham’s brass bolts, wire, lamps and chandeliers, nails, cabinet

and gas fittings were exported worldwide. Firms like

Winfield’s capitalised on the increasing popularity of brass bedsteads.

%2Bcasting%2Bengillmag1883.jpg) |

| Brass strip casting. |

|

| Making brass moulds. |

A government investigator interviewed adults and children at Winfield’s Cambridge St works in the 1860s (3rd Report, Children’s Employment Commission). Brass foundries were important employers for boys (girls worked in the packing rooms). Children started work around age 7, or more usually age 9 or 10.

The choking, poisonous fumes in the founding and casting shops

affected adult and child workers. The men making ‘yellow’ brass in particular

suffered from lung diseases. Henry Peel (27), a brass-caster at Timothy Smith

& Sons, said that ‘you get old’ at age forty: ‘I hope to live over 40’.

You can find out more about Birmingham brass manufacture, and how to

trace ancestors who worked in the industry, in the December issue of Who Do YouThink You Are? magazine.

Illustrations of brass strip casting, the brass workers' frieze, and the canals are from the English Illustrated Magazine, 1883. Making moulds and brass casting are from the Boys' Book of Trades, c.1890s. Author's collection.

Friday, 21 November 2014

Eloped!

Saddle up and gallop over to the British Newspaper Archive blog to read my guest post on a true-life thrilling 19th century elopement which could have come straight out of one of Jane Austen's novels!

Illustration by Hugh Thomson, Coaching Days and Coaching Ways, (Macmillan & Co. Ltd, 1910).

Illustration by Hugh Thomson, Coaching Days and Coaching Ways, (Macmillan & Co. Ltd, 1910).

Wednesday, 19 November 2014

Fairytale Gardens

|

| Lady's Monthly Museum, April 1805. |

Monday, 17 November 2014

Does Every Picture Tell A Story?

|

| Bridge St, Port Sunlight. |

Photo © Sue Wilkes.

Saturday, 8 November 2014

Austen Variations - And A Book Giveaway!

Today I'm a guest blogger on Austen Variations, courtesy of Jane Odiwe, whose new book Mr Darcy's Christmas Calendar is out now. Austen Variations, a website for writers and readers, focuses on 'Austen-related fiction, the Regency Period and Romance'. My guest post 'Chit-chat and Quarterly Reviews' looks at reading habits in Jane Austen's day. There's a competition to win a free copy of my new book A Visitor's Guide To Jane Austen's England, so do take time to leave a comment - it's free to enter!

Today I'm a guest blogger on Austen Variations, courtesy of Jane Odiwe, whose new book Mr Darcy's Christmas Calendar is out now. Austen Variations, a website for writers and readers, focuses on 'Austen-related fiction, the Regency Period and Romance'. My guest post 'Chit-chat and Quarterly Reviews' looks at reading habits in Jane Austen's day. There's a competition to win a free copy of my new book A Visitor's Guide To Jane Austen's England, so do take time to leave a comment - it's free to enter! The lucky winner will be announced on the Austen Variations Facebook page on 15 November.

Illustrations:

Title page of the Lady's Monthly Museum.

Tottenham High Cross in 1805, Gentleman's Magazine April 1820.

Thursday, 6 November 2014

Win A Free Copy of Tracing Your Ancestors' Childhood!

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Tracing Your Ancestors' Childhood

by Sue Wilkes

Giveaway ends November 27, 2014.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

Saturday, 1 November 2014

Going Shopping With Jane Austen!

|

| High Change in Bond St; Courtesy Library of Congress, |

The latest issue of Jane Austen's Regency World includes my feature on going shopping in Jane Austen's day, Maggie Lane explores the work of Elizabeth Inchbald, and Penny Townsend discusses Austen and William Shakespeare. There's also a review of my new book A Visitor's Guide To Jane Austen's England by Joceline Bury. Last but not least, the magazine has lots of wonderful Christmas gift ideas for Austen fans!

The latest issue of Jane Austen's Regency World includes my feature on going shopping in Jane Austen's day, Maggie Lane explores the work of Elizabeth Inchbald, and Penny Townsend discusses Austen and William Shakespeare. There's also a review of my new book A Visitor's Guide To Jane Austen's England by Joceline Bury. Last but not least, the magazine has lots of wonderful Christmas gift ideas for Austen fans!Tuesday, 28 October 2014

Dinnertime!

This week authors Sarah Murden and Joanne Major have very kindly invited me to write a guest post on the change in dining habits on their fabulous history blog All Things Georgian, so do check it out here!

Wednesday, 22 October 2014

Out Now!

My new book A Visitor's Guide to Jane Austen's England has just been released by Pen & Sword! You can also order a Kindle edition via Amazon. I hope you all enjoy reading my intimate look at daily life in Austen's day for the middle and upper classes.

My new book A Visitor's Guide to Jane Austen's England has just been released by Pen & Sword! You can also order a Kindle edition via Amazon. I hope you all enjoy reading my intimate look at daily life in Austen's day for the middle and upper classes.By the way, if you gallop post-haste to my Austen blog, my latest post on Jane and Bath is now online.

Sunday, 12 October 2014

Whiter Than White

As well as beautifully printed calicos and cottons, Georgian

and Victorian customers also wanted dazzling white cloth. Bleaching employed

‘great numbers of children and Young Persons’ in places like in Bolton and Bury, where most bleach-works and finishing

works were concentrated in 1850s Lancashire.

Traditionally, to bleach cloth, it was ‘bucked’ or ‘bowked,’ i.e.

soaked for several days in a strong, heated alkaline solution made from

vegetable ashes in a ‘kier’ or copper vessel. Then it was ‘soured’ to

neutralise the alkali by soaking it in buttermilk for at least a week.

‘Crofting’ was the next stage; the cloth was spread out

across the fields (bleaching croft), and soaked repeatedly with water, so the

sunlight could bleach it, which could take months. In late Georgian times,

industrial methods of bleaching were introduced which greatly speeded up this

process; artificial soda ash was used instead of vegetable-based alkalis, and

sulphuric acid was used instead of buttermilk. The invention of dash-wheels,

and later, washing machines, made it much easier to wash large quantities of

cloth (formerly done by hand by womenfolk in all weathers).

At the bleachworks, the ‘grey’ cloth was first sent to the

dressing-shop. The cloth was marked with the customer’s name or initials with a

needle. The ends of several pieces were sewn or pasted together to form one

long piece suitable for processing by machine; next, the cloth was ‘dressed’,

that is, passed over a hot plate or gas jets to singe off nwanted fibres.

After dressing, the cloth was bleached as above, then went

through the finishing processes: mangling, drying and clamping (stretching),

beetling, calendering (an ironing process in which the cloth passed between

heated rollers to give it a glossy finish), then making up and packing. Beetling was a special, lustrous finish for

Holland cloth used for blinds, achieved by hammering the cloth

Hours were exceedingly irregular; in the 1850s fourteen year

old Mary Partington’s hours varied anything between 56 hours and 76 hours per

week at Ridgway Bridson Bleachworks, Bolton, which employed over 200 people.

You can find out more about the story of the industrial revolution in Lancashire here, tracing Lancashire ancestors here, and the fight to improve children’s working

hours and conditions in The Children History Forgot.

Illustrations from author’s collection.

Llewenni (Lleweni) Bleachworks, Denbighshire, designed by

Thomas Sandby for Thomas Fitzmaurice. Engraving by Thomas Sandby, 1792. Possibly one of the grandest bleachworks ever

built.

Dash wheels, and Calendering. Pictorial History of Lancashire, 1844.

Dash wheels, and Calendering. Pictorial History of Lancashire, 1844.

Friday, 10 October 2014

Austen Blog Update

|

| Assembly Rooms, Bath. |

Monday, 29 September 2014

Calico Print Workers

My latest feature for Who Do You Think You Are? magazine (October issue) is about Lancashire calico-printing workers, and how to research your ancestors in that branch of the textile industry.

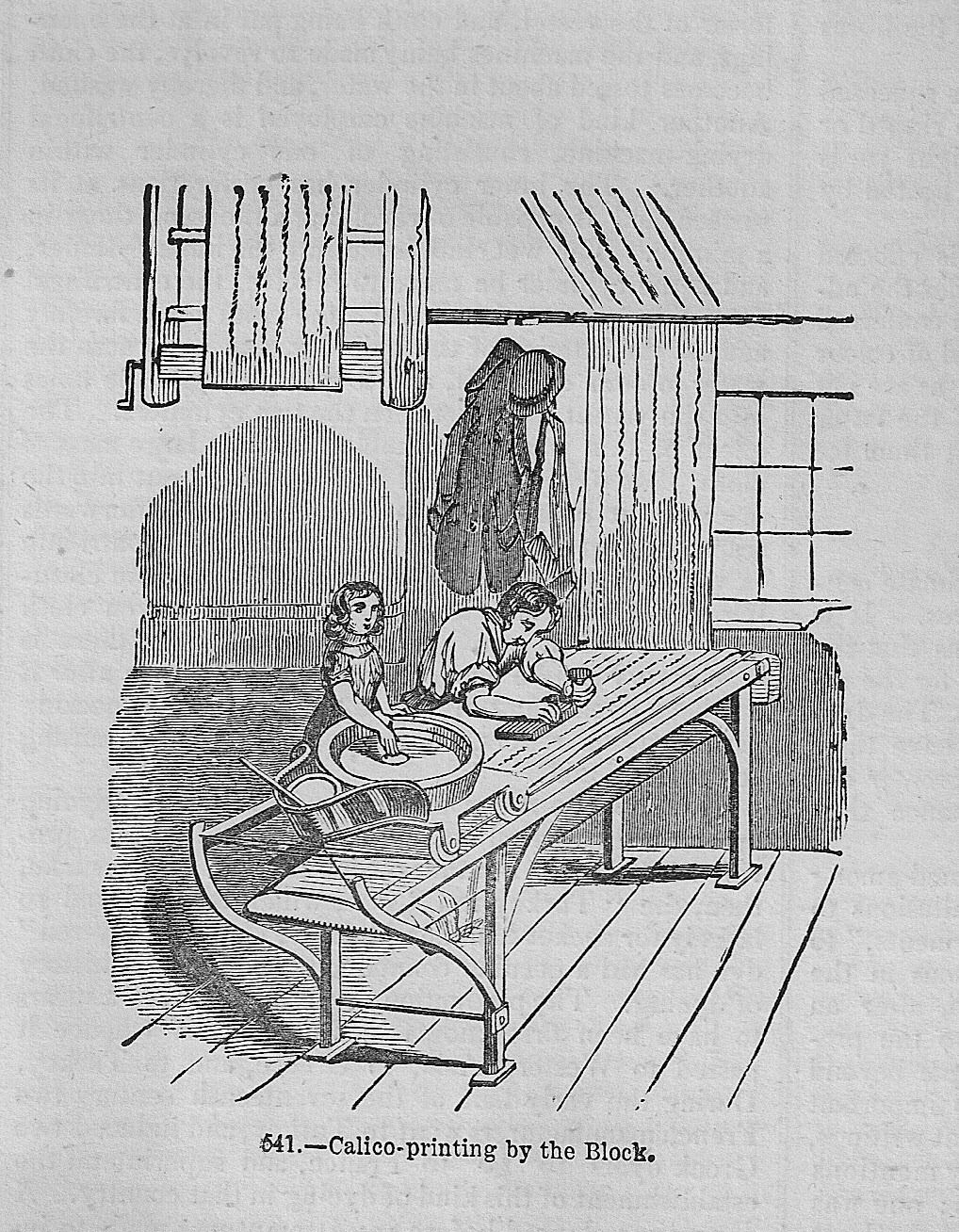

Originally, calico was printed by hand. The cloth was stretched across a printing table, wound round a roller at each end so that the cloth could be wound on ready for the next length to be printed. The printer had a child helper, a ‘tierer’, who dipped a small brush in a pot of colour, then brushed the liquid colour evenly onto a sieve or drum floating on a bed of water. The printer then placed an engraved wooden block or copper plate (with a handle on the back), onto the sieve so that it picked up the dye. The block was then pressed firmly onto the fabric to create a pattern. Block-printing was a slow process; it could take all day to produce just six pieces of cloth printed with a plain pattern

The first recorded calico printer in Manchester is William Jordan, ‘callique-printer’ at Little Green in 1763; the trade in Lancashire gained a strong foothold the following year at Clayton’s factory in Bamber Bridge, near Preston.

The days of block

printing were numbered when roller or cylinder-printing was patented by Thomas Bell in 1783. A rotating cylinder was dipped into a trough of colour dye; next, a long steel

rule or ‘doctor’ removed excess colour from the cylinder. The cloth to be

printed was pressed against the dye on the engraved cylinder by means of a

roller, so that the pattern was continuously printed on it as it moved along. Children were employed in the print-work factories, too.

The days of block

printing were numbered when roller or cylinder-printing was patented by Thomas Bell in 1783. A rotating cylinder was dipped into a trough of colour dye; next, a long steel

rule or ‘doctor’ removed excess colour from the cylinder. The cloth to be

printed was pressed against the dye on the engraved cylinder by means of a

roller, so that the pattern was continuously printed on it as it moved along. Children were employed in the print-work factories, too.

Now hundreds of pieces of cloth could be printed in a day.

Hoyle’s Mayfield works at Manchester employed over 200 workers in the 1830s, including over 40 children; the children earned 2s 6d per week when learning the trade, then 3s 6d when ‘fully instructed.’

You can find out more about the lives of child print-workers in my book Young Workers of the Industrial Age, and the Lancashire textile industry here.

Illustrations from author's collection:

Originally, calico was printed by hand. The cloth was stretched across a printing table, wound round a roller at each end so that the cloth could be wound on ready for the next length to be printed. The printer had a child helper, a ‘tierer’, who dipped a small brush in a pot of colour, then brushed the liquid colour evenly onto a sieve or drum floating on a bed of water. The printer then placed an engraved wooden block or copper plate (with a handle on the back), onto the sieve so that it picked up the dye. The block was then pressed firmly onto the fabric to create a pattern. Block-printing was a slow process; it could take all day to produce just six pieces of cloth printed with a plain pattern

The first recorded calico printer in Manchester is William Jordan, ‘callique-printer’ at Little Green in 1763; the trade in Lancashire gained a strong foothold the following year at Clayton’s factory in Bamber Bridge, near Preston.

The days of block

printing were numbered when roller or cylinder-printing was patented by Thomas Bell in 1783. A rotating cylinder was dipped into a trough of colour dye; next, a long steel

rule or ‘doctor’ removed excess colour from the cylinder. The cloth to be

printed was pressed against the dye on the engraved cylinder by means of a

roller, so that the pattern was continuously printed on it as it moved along. Children were employed in the print-work factories, too.

The days of block

printing were numbered when roller or cylinder-printing was patented by Thomas Bell in 1783. A rotating cylinder was dipped into a trough of colour dye; next, a long steel

rule or ‘doctor’ removed excess colour from the cylinder. The cloth to be

printed was pressed against the dye on the engraved cylinder by means of a

roller, so that the pattern was continuously printed on it as it moved along. Children were employed in the print-work factories, too.Now hundreds of pieces of cloth could be printed in a day.

Hoyle’s Mayfield works at Manchester employed over 200 workers in the 1830s, including over 40 children; the children earned 2s 6d per week when learning the trade, then 3s 6d when ‘fully instructed.’

You can find out more about the lives of child print-workers in my book Young Workers of the Industrial Age, and the Lancashire textile industry here.

Illustrations from author's collection:

Block printer and tierer or ‘tear girl’ (above, left). Children as young

as six worked for twelve hours or more helping block printers. Charles Knight’s

Pictorial Gallery of Arts Vol. I, (c.1862).

A calico printworks at Manchester in the 1890s (above, right), and a view of Hoyle's printworks from London Rd Station (left). Both illustrations by H E Tidmarsh, Manchester Old and New Vol. II, (Cassell &

Co., c. 1894).