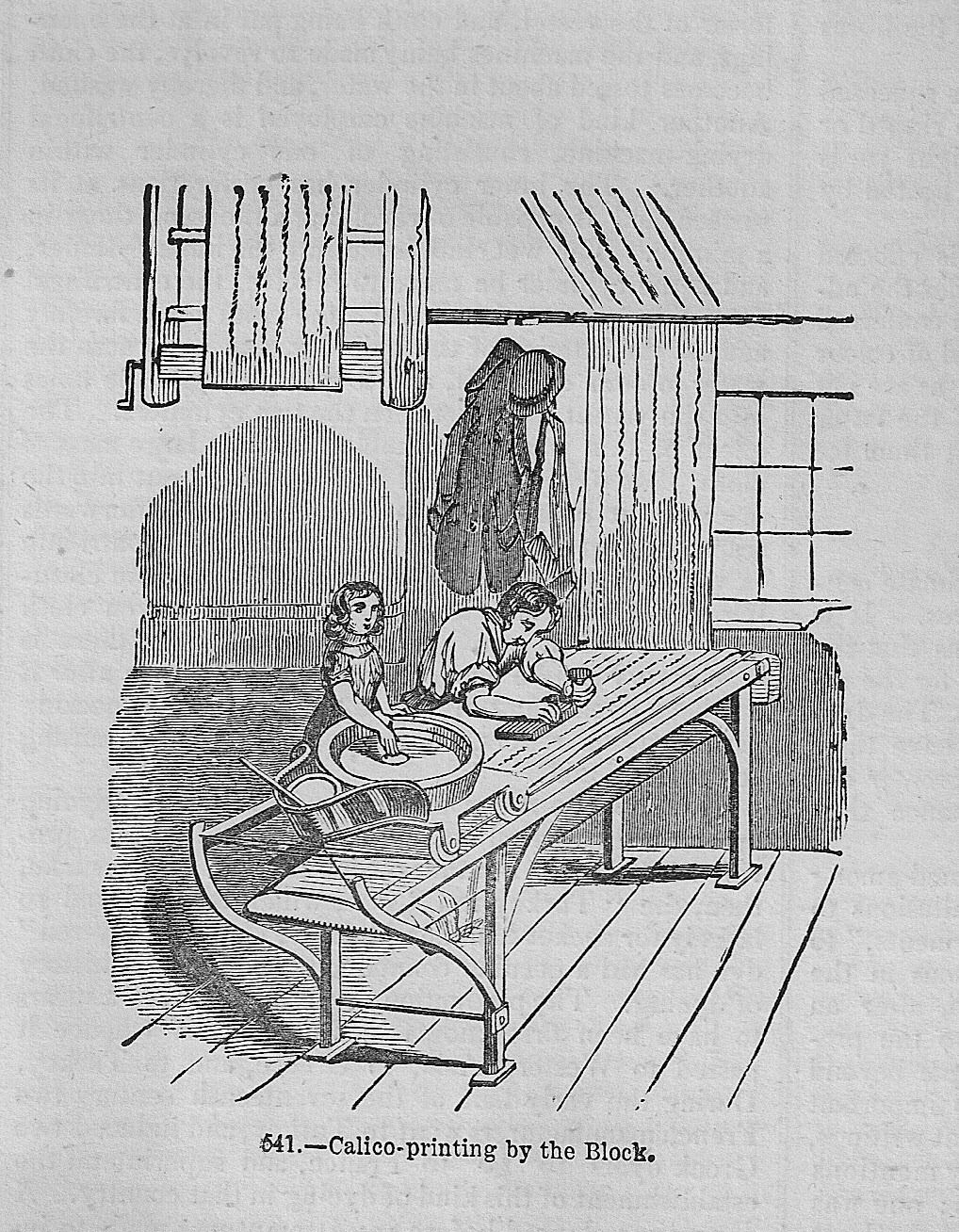

Originally, calico was printed by hand. The cloth was stretched across a printing table, wound round a roller at each end so that the cloth could be wound on ready for the next length to be printed. The printer had a child helper, a ‘tierer’, who dipped a small brush in a pot of colour, then brushed the liquid colour evenly onto a sieve or drum floating on a bed of water. The printer then placed an engraved wooden block or copper plate (with a handle on the back), onto the sieve so that it picked up the dye. The block was then pressed firmly onto the fabric to create a pattern. Block-printing was a slow process; it could take all day to produce just six pieces of cloth printed with a plain pattern

The first recorded calico printer in Manchester is William Jordan, ‘callique-printer’ at Little Green in 1763; the trade in Lancashire gained a strong foothold the following year at Clayton’s factory in Bamber Bridge, near Preston.

The days of block

printing were numbered when roller or cylinder-printing was patented by Thomas Bell in 1783. A rotating cylinder was dipped into a trough of colour dye; next, a long steel

rule or ‘doctor’ removed excess colour from the cylinder. The cloth to be

printed was pressed against the dye on the engraved cylinder by means of a

roller, so that the pattern was continuously printed on it as it moved along. Children were employed in the print-work factories, too.

The days of block

printing were numbered when roller or cylinder-printing was patented by Thomas Bell in 1783. A rotating cylinder was dipped into a trough of colour dye; next, a long steel

rule or ‘doctor’ removed excess colour from the cylinder. The cloth to be

printed was pressed against the dye on the engraved cylinder by means of a

roller, so that the pattern was continuously printed on it as it moved along. Children were employed in the print-work factories, too.Now hundreds of pieces of cloth could be printed in a day.

Hoyle’s Mayfield works at Manchester employed over 200 workers in the 1830s, including over 40 children; the children earned 2s 6d per week when learning the trade, then 3s 6d when ‘fully instructed.’

You can find out more about the lives of child print-workers in my book Young Workers of the Industrial Age, and the Lancashire textile industry here.

Illustrations from author's collection:

Block printer and tierer or ‘tear girl’ (above, left). Children as young

as six worked for twelve hours or more helping block printers. Charles Knight’s

Pictorial Gallery of Arts Vol. I, (c.1862).

A calico printworks at Manchester in the 1890s (above, right), and a view of Hoyle's printworks from London Rd Station (left). Both illustrations by H E Tidmarsh, Manchester Old and New Vol. II, (Cassell &

Co., c. 1894).